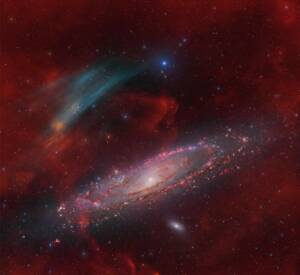

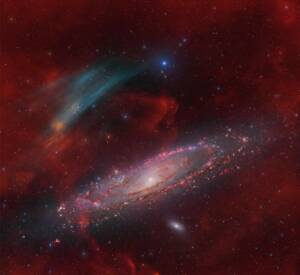

Discovery of the M31 [OIII] emission arc

Recently, a major discovery by an international team of amateur astronomers and scientists has become a huge online hit, and this new discovery is just located in one of the

Hello Brennan, thanks for accepting our interview invitation. Congratulations on winning the ASIWEEK competition in week #04/2024!

My name is Brennan Gilmore. I am 44 years old and live in Virginia in the United States. I am currently the director of an environmental organization and for many years worked as a diplomat, primarily in sub-Saharan Africa. I’m also a part-time musician, and play guitar and mandolin. Apart from astrophotography, my hobbies include woodworking, hunting, fishing and breeding heritage chickens.

The summer of 2020 was marked by the passage of the brilliant Comet Neowise. Locked down during the pandemic, I set out to capture this rare visitor to our corner of the solar system. A friend and professional photographer, Sanjay Suchak, generously lent me equipment and helped me to understand how I might capture the comet.

I spent the next month chasing Neowise from night to morning, studying astrophotography by day and shooting the comet by night. Neowise eventually faded, but my passion for astrophotography had ignited.

I live in a Bortle 4 zone in central Virginia, which allows for relatively good sky conditions to shoot, and this is where my home observatory is. For darker skies I often travel a couple hours to the Virginia/West Virginia border where I can shoot under Bortle 2 skies at a friend’s farm in Highland County, Virginia.

The winning photo is of the Soul Nebula, IC 1848, a very popular target in the northern skies, located in Cassiopeia next to its famous partner, the Heart Nebula. For this photo I decided to go much deeper than I usually do in integration time. For most of my deep sky photos I tend to stop after 15-20 hours. For this image, I collected over 20 hours of each narrowband wavelength: Ha, Sii, and Oiii. I then shot 90 x 30s of RGB for the stars. The final image was a 62 hour integration.

I have several different set-ups depending on what I’m shooting. For deep-sky, I most often use a Sky-Watcher Esprit100ED refractor, Chroma 3nm narrowband and RGB filters in a ZWO filter wheel, and a ZWO ASI2600MM-Pro. This sits on a SW EQ6R-Pro mount and I use a ZWO OAG and an ASI174MM for guiding. For comets I use a ZWO ASI294MC, as processing comets with an OSC camera is far more efficient than in mono.

For galaxies and planets I switch out the OTA with a Celestron EdgeHD 9.25.

For landscape and wide-angle astrophotography I use a Sony A7III that has been Ha modified, along with a range of Sony GM lenses – 16mm, 24m, 35mm, 50mm, 85mm, and 200-600mm zoom. The only non-Sony lenses I use are an Askar FMA180 (which I adore) and a Rokinon 135mm.

The hardest part of astrophotography is the learning curve. It takes a long time to build up the technical knowledge and master your equipment, as well as learn processing techniques. That said, while it can be frustrating, the learning process is extremely fun and rewarding, spending many nights under starry skies, contemplating simultaneously our cosmic existence and why my computer will not recognize a new USB driver.

I love all types of astrophotography from landscape to planets to nebulae to galaxies. My favorite if I had to choose would be photographing comets. These icy, luminiferous visitors are not only stunningly beautiful, but unpredictable and constantly changing as they are battered by solar winds. Comets also challenge my astrophotography skills, as every aspect of the process, from acquisition to processing, is more difficult than other deep sky targets. I spent many nights in late 2022 and early 2023 photographing C/2022 E3 (ZTF) and learned a lot over these months. Some of my photographs of this comet were featured in national media stories about the comet, including a timelapse of separation of the comet’s tail, which was one of the most intensive astrophotography projects I’ve done.

After chasing Comet Neowise for a month, it was set to align perfectly with one of my favorite areas in Virginia – Goshen Pass on the Maury River, where I grew up. I had only one night to shoot it over the river, so I drove with a friend to the area early in the afternoon to set up. Almost immediately we ran into trouble. First, my friend was nearly bit by a poisonous copperhead snake that fell from one of the many rocks by the riverside as we waited for nightfall. Then, after wading out into the middle of the river with my camera gear to set it up on a midstream boulder, I slipped on the algae-covered stones and almost doused a few thousand dollars of borrowed gear. Once all the gear was ready to go, I heard the distant rumble of thunder. Within minutes, a huge storm popped up, and we had to quickly break down the gear, scurry out of the river and seek shelter in my truck. Night came, and it looked like I would lose the opportunity to shoot the comet due to the intense storm. I was ready to pack it in and begin the two-hour drive home, defeated, but my friend convinced me to wait it out just in case the clouds broke in time. Thankfully I listened to her, because with only minutes to spare, the clouds disappeared revealing the massive comet stretching across the sky. I jumped back into the river and hurriedly set up my camera equipment and began shooting. Almost as an afterthought I asked my friend to wade into the water to be in a photo. She agreed, which was quite brave considering it was pitch dark and she’d almost been bitten by a snake in those same river rocks a few hours earlier. Just as the comet began to set, I was able to capture the perfect alignment as she held her balance in the rushing water and absorbed the view during a minute-long exposure. I had only been a photographer for a few weeks, and was still using a friend’s equipment, so I was thrilled with the result!

I participate in exoplanet transit research using photometry, and have been contributing to programs that aid professional astronomers in refining transit times to increase efficiency with very limited and expensive space telescope time. Some of my exoplanet transit confirmations are now credited by NASA through its partnership with the American Association of Variable Star Observers (GBRD is my observer code in the linked database). This is a fascinating area of astronomy that amateurs can do with regular equipment. It’s pretty incredible to be able to “see” via photometry planetary worlds many light years away that may even harbor life. All of my exoplanet research has been done with a ZWO ASI2600MM-Pro.

My first ASI camera was a 1600MM-Pro. I decided to jump into the deep end with mono imaging from the start, and still shoot mono for everything except comets and landscapes. I currently own four ASI cameras: 2600MM-Pro, 294MC, 174MM, and 120MM-S along with a ZWO filter wheel, OAG and mini guide scope.

I started using ZWO when I first began deep sky astrophotography in September 2020, and have exclusively used ZWO cameras for deep sky ever since. I absolutely love my 2600MM-Pro – the quantum efficiency and image quality are stunning and it is a very durable camera that has endured every weather condition Virginia throws at it. My only advice is to introduce a rotator – this is the one aspect of imaging that I have yet to automate.

Don’t get frustrated! The learning curve is steep because of the enormous amount of variables and steps in creating a final image you can be proud of. The flipside of this is that the learning curve is very fun. Nights spent outside under the stars are much better than nights spent inside under a roof!

Recently, a major discovery by an international team of amateur astronomers and scientists has become a huge online hit, and this new discovery is just located in one of the

1.How It All Began I have been a fan of astronomy since high school.Starting from a school event where I can see the moon up close through a telescope.When I

1. How It All Began For Puig Nicolas, it all started at the age of 10 with a 60/700 refractor and a 114/900 reflector. His first celestial encounters — the

By day, David Cruz works as a digital designer. By night, he designs something far greater — images of the universe itself. “Since I was young, I was always interested

bbrown_admin, October 30, 2025 INITIAL IMPRESSIONS: The ZWO ASI585MC Air came well packaged from the manufacturer. The box is improved and has an impressive feel with a magnetic closure on

– Q3 ASIWEEK Winner Gianni Lacroce’s Astrophotography Journey Hi, I’m Gianni Lacroce, an Italian astrophotographer. My passion for the night sky began long before I owned a telescope or a